With concentration levels increasing in stock markets around the world, investors in passive equity strategies are taking on ever more risk, argues Richard Saldanha.

3 minute read

In August 2018, Apple became the world’s first trillion-dollar public company, just 42 years after being founded in the garage of former boss Steve Jobs. Barely a month later, Amazon passed the same milestone – 18 years quicker. The companies’ combined market value, if translated into national income, would have made them the world’s tenth biggest economy, with each alone bigger than Turkey’s.

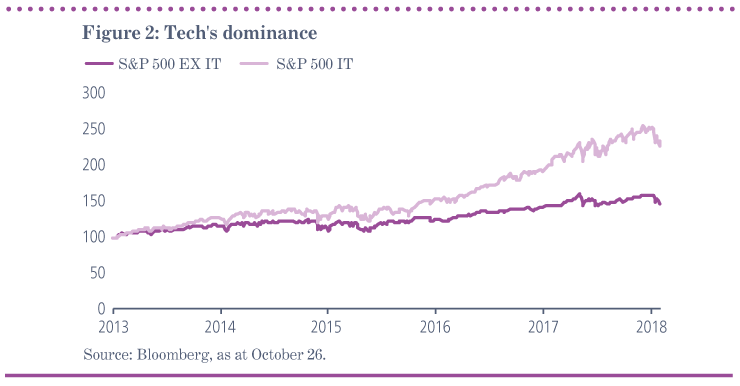

The rapid growth in these two firms’ market value – along with those of other technology giants such as Microsoft, Alphabet, and Facebook – has in recent years delivered handsome returns to many investors. Simultaneously, it is causing concern on many fronts.

Echoes of the dot.com bubble

Since it has helped drive concentration levels within the US stock market to what are arguably unprecedented levels, from an investor’s perspective the dominance of these big technology firms is becoming more of an issue.

As at the end of September, the top five companies in the S&P 500 accounted for 15.8 per cent of the index’s market capitalisation. That left it just shy of the previous peak in early 2000, at the height of the dot.com boom, which itself was the highest level in 18 years.

While it is true the biggest five stocks accounted for an even larger slice of the US market in the 1960s and 1970s, what makes the current situation unique is the dominance of just one sector – technology. Of the largest five US groups, only Berkshire Hathaway is not a technology company. Facebook, the sixth biggest, is only slightly smaller than Warren Buffet’s investment vehicle following a recent decline in its share price. By contrast, even in early 2000, only two technology groups – Microsoft and Intel – ranked among the top six.

Between them, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook and Alphabet accounted for 15.7 per cent of the S&P 500 at the end of September. When including the latter three stocks, the technology sector comprised 29 per cent of the index, as much as in early 2000.1 That left it exceeding the next two largest sectors – financial services and pharmaceuticals – combined.

A global phenomenon

Worryingly, stock markets are even more concentrated in many other places. For instance, the top five stocks constitute nearly 18 per cent of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, with the technology sector once again dominant. As for the UK, five biggest companies account for nearly a third of the FTSE 100.

Such high levels of stock market concentration are partly a result of the growing prevalence of passive investment vehicles. According to Morningstar, by the end of 2017, passive investments accounted for almost 45 percent of all equity assets in US mutual funds and exchange-traded products.2 The fact most leading indices such as the S&P 500 and FTSE 100 are weighted according to constituent members’ market capitalisations means the biggest shares attract ever more money from tracking funds as their price rises.

The obvious danger is that asset price ‘momentum’ becomes a key driver of future asset price returns, irrespective of the underlying performance of the company itself. In such an environment, where passive funds begin to monopolise investment flows, there can be a large divergence between companies’ market capitalisation and their true economic worth.

The other problem posed by rising stock market concentration is that many investors in passive investment vehicles are unlikely to be aware of the level of risks they are exposed to.

There is a widespread perception that index-tracking products are less risky than their actively-managed cousins since the latter tend to be more concentrated. While that may be true of an index where all the constituent stocks are of a roughly similar size, the reverse may be the case in an environment where the stock index itself has become highly concentrated.

For instance, it seems likely many investors in passive investment vehicles tracking the S&P 500 have, in technology, got much more exposure to a single sector than they are aware of. And as share prices in the sector rise, so too does the size of the bet on that sector.

History repeats?

While there may be strong fundamental reasons to explain the surge in technology stock valuations in recent years, history demonstrates markets do not go up for ever. Common sense suggests the sector that led the market higher will be the one that suffers oversized losses when sentiment sours, as was the case with energy stocks in the early 1980s, technology shares in 2000 and financials in 2008.

There is nothing to suggest such a reversal in the technology sector’s fortunes is imminent. Nevertheless, the dangers posed by increased stock market concentration help explain the growing popularity of alternative beta strategies. To avoid the dangers of following stock price momentum, managers of such funds will often anchor positions based on fundamental factors such as revenues or profits, rather than market capitalisation.

The dangers posed by rising stock market concentration could tip the balance once again to active managers over their passive rivals. Active managers who are rigorous in their analysis of the fundamental drivers of companies’ value, and remain disciplined on the price they pay, seem well-placed to benefit from any market inefficiencies.

References

1 According to S&P Dow Jones Indices and MSCI, Amazon is in the consumer discretionary sector, while Alphabet and Facebook were recently moved from the technology sector to a newly created communication services sector.

2 ’Passive Investing Rises Still Higher, Morningstar Says,‘ Institutional Investor, 21 May 2018

Source for all market returns data: Bloomberg

Source for all index composition data: Factset