The big picture

Policies coming into focus

The global economy looks to be in slightly better shape than we had anticipated three months ago. That is thanks to the US and Chinese economies having performed somewhat better at the end of 2023 and in the first quarter than envisaged. We expect global output to expand 3 per cent in 2024, higher than our expectation of 2.75 per cent at the start of the year.

The US consumer remains in a healthy position, with real disposable income rising at a solid pace, driven by ongoing employment and wage gains and helped by a moderation in inflation. The corporate sector is also on an improving trajectory, with profits rising and investment spending supported by government policies.

The Eurozone is expected to have returned to growth in the first quarter, following a year of stagnation. Supported by historically low unemployment rates and elevated household savings, consumer spending should pick up as the impact of higher energy prices fades. The UK economy should also return to growth in the first quarter, although the picture is not quite so bright given the ongoing impact of higher mortgage rates. The outlook for Japan is also positive, although growth may struggle to match last year’s pace.

While headline rates of inflation have continued to fall, in a continuation of last year’s trend, the strength of labour markets has ensured service sector inflation has stayed stubbornly high. That in turn means headline inflation rates are still above central banks’ targets of around two per cent and could remain so for a while longer yet.

Financial markets have in recent weeks begun to acknowledge the reality of higher inflation by recalibrating the outlook for interest rates. The expectation is that the first cut in rates will be delayed and that thereafter rates are unlikely to fall in the current economic cycle by as much as previously anticipated.

That said, the picture is not uniform. The strength of the US economy means financial markets may have to scale back their expectation of looser monetary policy further, whereas the opposite is arguably the case in the UK given the comparatively weak economic backdrop.

Figure 1: Aviva Investors growth projections

Future statements are not reliable indicators of future performance or future scenarios.

Source: Aviva Investors, Macrobond. Data as of March 31, 2024.

What this means for asset allocation

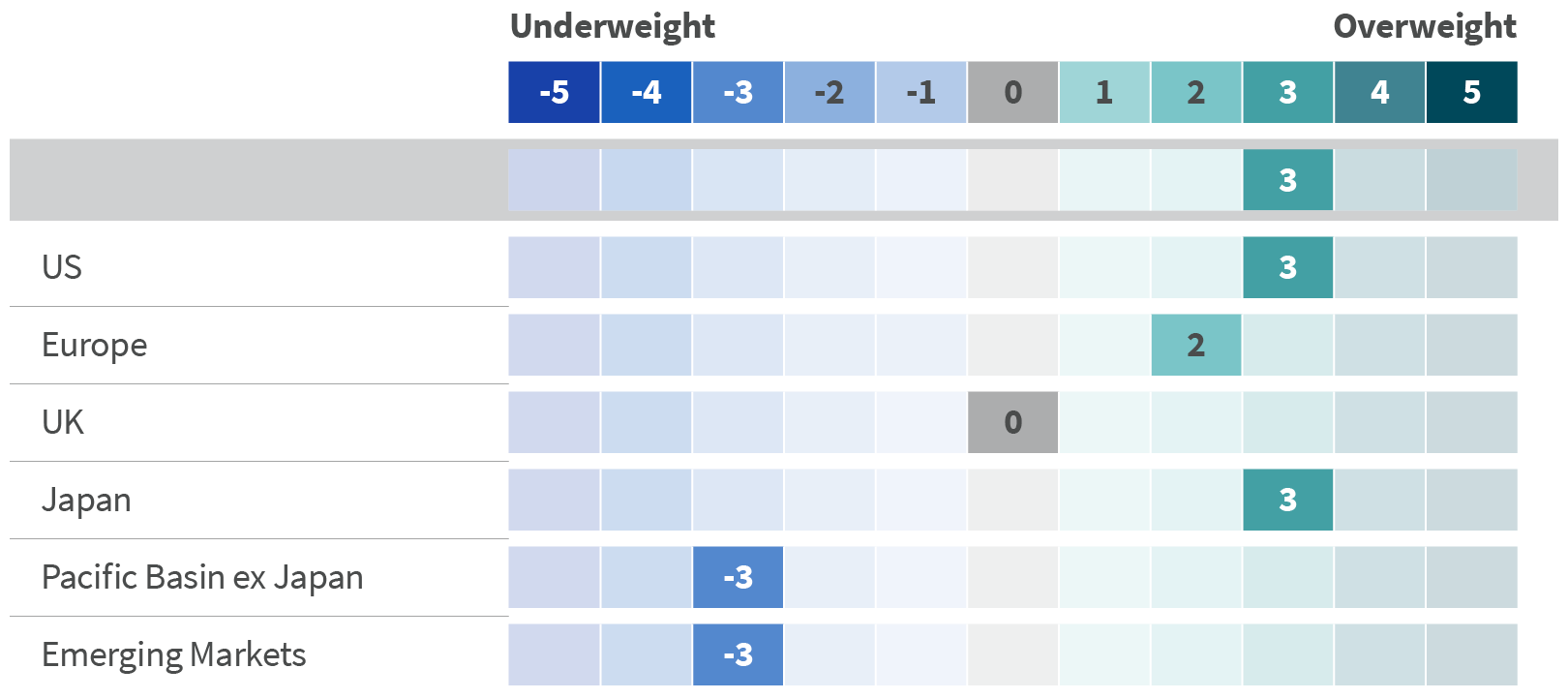

Equities

The beginning of 2024 has seen equities powering ahead, buoyed by an improved economic outlook, particularly in the US, and healthy growth in corporate profits. Although valuations are not cheap, especially in the US, we see further upside potential for equity markets. We see greater value in developed equity markets such as the US, Japan and continental Europe than in their emerging-market peers. We are cautious on the UK stock market owing to concern over the domestic economy.

Having said this, we believe equity markets will struggle to go on rising at their current pace for much longer. Should they do so, our concern would be that markets were at risk of a sizeable correction.

Figure 2: Asset allocation - Equities

Note: The weights in the Asset allocation table only apply to a model portfolio without mandate constraints. Our House View asset allocation provides a comprehensive and forward-looking framework for discussion among the investment teams.

Source: Aviva Investors. Data as of March 31, 2024.

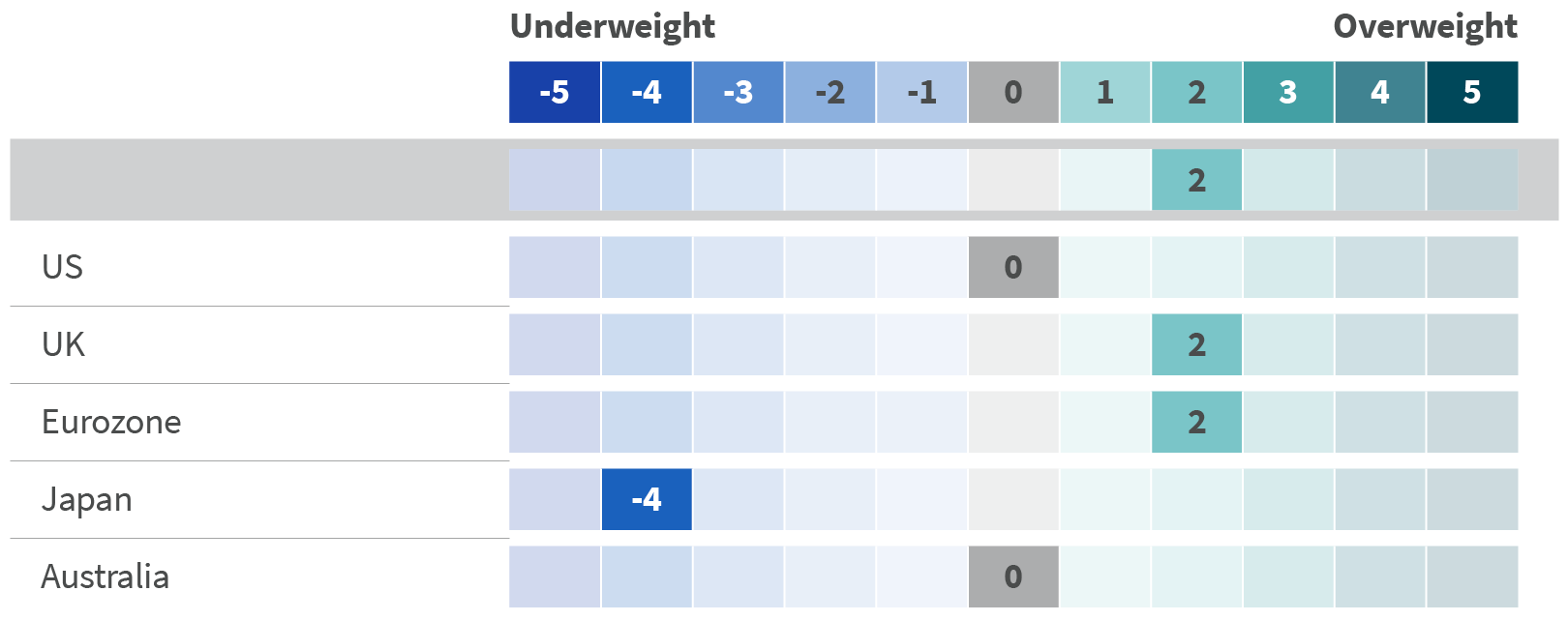

Government bonds

Government bonds have sold off sharply this year, responding to evidence that leading economies, especially the US, were not slowing as much as expected and that inflation was proving sticky. As a result, market expectations as to the pace and magnitude of rate cuts look more sensible, which means value is starting to appear in some markets.

Our concern that equities could eventually be at risk of a sizeable correction, should current levels of ebullience persist, informs our view that government bonds appear to offer an attractive means of diversifying multi-asset portfolios at present. All the more so given the magnitude of the rise in yields over the past two years as bonds sold off sharply. This makes for an attractive risk/reward picture as we enter a rate-cutting cycle.

We especially like the UK market as we believe in this case rates could fall by more than is anticipated given economic prospects. European markets also offer value, albeit less so. By contrast, Japanese bonds continue to look expensive after the Bank of Japan ended eight years of negative interest rates.

Figure 3: Asset allocation - Government bonds

Note: The weights in the Asset allocation table only apply to a model portfolio without mandate constraints. Our House View asset allocation provides a comprehensive and forward-looking framework for discussion among the investment teams.

Source: Aviva Investors. Data as of March 31, 2024.

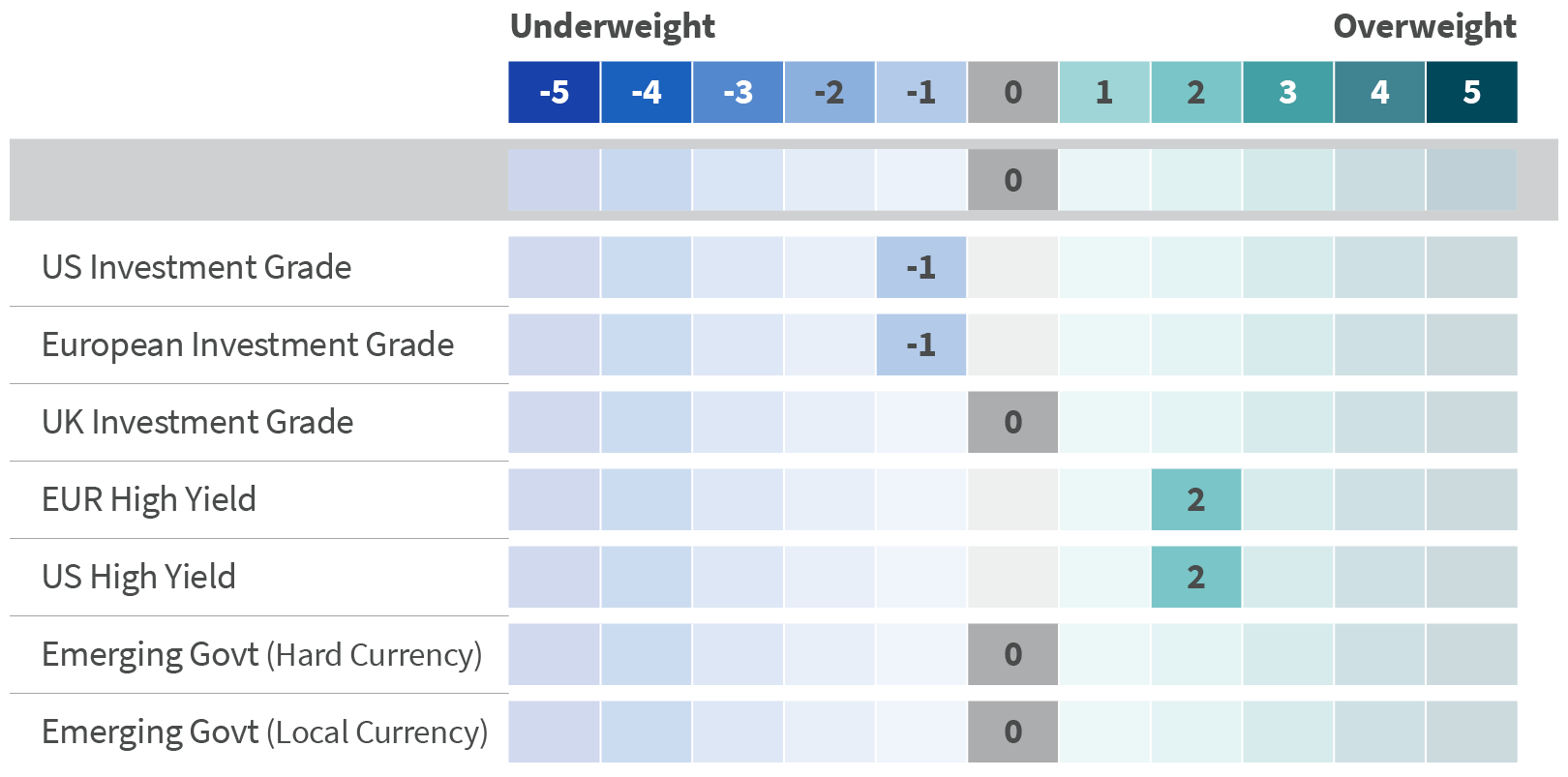

Credit

We continue to prefer to be broadly neutral on corporate bonds. On the one hand it is hard to see why the extra return investors demand to own corporate debt relative to safer government debt will rise appreciably given the favourable economic backdrop. Most companies are not carrying excessive amounts of debt on their balance sheets, and recent company results on balance were healthy with earnings generally surpassing expectations. Then again, the extra yield investors are being offered to own corporate debt is unappealing.

Our multi-asset portfolios tend to favour high-yield debt issued by less creditworthy companies. Given the largely positive economic backdrop, they appear to offer better value than investment-grade bonds issued by more highly rated companies.

Figure 4: Asset allocation - Credit

Note: The weights in the Asset allocation table only apply to a model portfolio without mandate constraints. Our House View asset allocation provides a comprehensive and forward-looking framework for discussion among the investment teams.

Source: Aviva Investors. Data as of March 31, 2024.

Key investment themes

1. Rate cuts coming, sooner or later

The main market theme for 2024 remains the prospect of cuts in interest rates by central banks in developed countries. While cutting rates while inflation remains elevated and labour markets tight is a risk, so is leaving rates too high for too long

Having kept rates too low for too long in 2021, continuing to fight the last battle and inducing a recession – or being blamed for it – would be an equally serious error for central banks to make.

Nonetheless, policymakers need to take care. Once banks do begin cutting rates, the so-called normalisation process could be prolonged and bumpy and potentially diverge appreciably from country to country. The prospect is for faster easing in Europe and the UK than in the US, Canada, and Australia.

Figure 5: “Low” expectations as many rate cuts are priced in across G10 markets

Source: Aviva Investors, Bloomberg. Data as of March 31, 2024.

2. Geopolitical tension and financial fragmentation: The centre isn’t holding

This year is full of consequential elections, but even if one correctly predicts a given outcome, its impact, not to mention the market reaction to it, are not always easy to forecast. Mass immigration and threats to borders have been upending domestic politics across the West for some time and look likely to continue to do so.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has shone a spotlight on the extent to which many nations have been relying on countries controlled by dictators or unelected autocrats for the supply of carbon-based fuels.

Globalisation, as measured by trade and capital flows, is still alive, yet significant changes are underway. Multinationals are adjusting their supply chains and diversifying away from China for a variety of reasons. Tariffs, sanctions, and countersanctions have proliferated, as have subsidies, as governments strive to bolster domestic firms’ capabilities in sectors such as technology, energy and defence equipment.

Figure 6: World trade volumes still near records, despite tariffs and sanctions

Source: Aviva Investors, CPB World Trade Monitor, US Treasury, Census Bureau, Macrobond. Data as of March 31, 2024.

3. Industrial policy: Looking up and pushing forward

Governments have been turning to various forms of intervention and industrial policies as they increasingly focus on long-term national and economic security objectives and combatting climate change. While such policies are not particularly groundbreaking, it is their scale and scope that makes them extraordinary.

The aggressive nature of China’s subsidies and technological aims, such as “Made in 2025”, as well as the removal of fiscal shackles following the pandemic, has triggered a response from developed nations in the form of more explicit and muscular industrial policies. Most big economic powers plan to spend vast sums or provide enormous tax breaks to deliver these objectives.

Will these policies become inflationary boondoggles? As there is a risk that much of the money goes to waste, governments will want to ensure they are focused and don’t set multiple objectives for these projects, consult sufficiently with businesses, local stakeholders and policy experts, and are prepared to let losing projects fail.

Industrial policies have become explicit and muscular, but will they also become inflationary boondoggles?

Read the House View

House View Q2 2024

The first quarter of 2024 has seen growth momentum maintained or moderately improve across most regions.

Never miss the latest House View

Sign-up to receive quarterly emails on our collective view of global markets.

Webcast: House View Q2 2024

Join us for our live House View Q2 2024 webcast, where Thomas Stokes, Investment Director, Multi-assets; Vasileios Gkionakis, Senior Economist; and Guillaume Paillat, Multi- Asset Portfolio Manager, discuss the latest economic changes that impact asset allocation in 2024.

About the House View

The Aviva Investors House View document is a comprehensive compilation of views and analysis from the major investment teams.

The document is produced quarterly by our investment professionals and is overseen by the Investment Strategy team. We hold a House View Forum biannually at which the main issues and arguments are introduced, discussed and debated. The process by which the House View is constructed is a collaborative one – everyone will be aware of the main themes and key aspects of the outlook. All team members have the right to challenge and all are encouraged to do so. The aim is to ensure that all contributors are fully aware of the thoughts of everyone else and that a broad consensus can be reached across the teams on the main aspects of the report.

The House View document serves two main purposes. First, its preparation provides a comprehensive and forward-looking framework for discussion among the investment teams. Secondly, it allows us to share our thinking and explain the reasons for our economic views and investment decisions to those whom they affect.

Not everyone will agree with all assumptions made and all of the conclusions reached. No-one can predict the future perfectly. But the contents of this report represent the best collective judgement of Aviva Investors on the current and future investment environment.

House View contributors

Michael Grady

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

David Nowakowski

Senior Strategist, Multi-asset & Macro

Joao Toniato

Head of Global Equity Strategy

Vasileios Gkionakis

Senior Economist and Strategist

Important information

THIS IS A MARKETING COMMUNICATION

Except where stated as otherwise, the source of all information is Aviva Investors Global Services Limited (AIGSL). Unless stated otherwise any views and opinions are those of Aviva Investors. They should not be viewed as indicating any guarantee of return from an investment managed by Aviva Investors nor as advice of any nature. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but has not been independently verified by Aviva Investors and is not guaranteed to be accurate. Past performance is not a guide to the future. The value of an investment and any income from it may go down as well as up and the investor may not get back the original amount invested. Nothing in this material, including any references to specific securities, assets classes and financial markets is intended to or should be construed as advice or recommendations of any nature. Some data shown are hypothetical or projected and may not come to pass as stated due to changes in market conditions and are not guarantees of future outcomes. This material is not a recommendation to sell or purchase any investment.

The information contained herein is for general guidance only. It is the responsibility of any person or persons in possession of this information to inform themselves of, and to observe, all applicable laws and regulations of any relevant jurisdiction. The information contained herein does not constitute an offer or solicitation to any person in any jurisdiction in which such offer or solicitation is not authorised or to any person to whom it would be unlawful to make such offer or solicitation.

In Europe, this document is issued by Aviva Investors Luxembourg S.A. Registered Office: 2 rue du Fort Bourbon, 1st Floor, 1249 Luxembourg. Supervised by Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier. An Aviva company. In the UK, this document is by Aviva Investors Global Services Limited. Registered in England No. 1151805. Registered Office: 80 Fenchurch Street, London, EC3M 4AE. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Firm Reference No. 119178. In Switzerland, this document is issued by Aviva Investors Schweiz GmbH.

In Singapore, this material is being circulated by way of an arrangement with Aviva Investors Asia Pte. Limited (AIAPL) for distribution to institutional investors only. Please note that AIAPL does not provide any independent research or analysis in the substance or preparation of this material. Recipients of this material are to contact AIAPL in respect of any matters arising from, or in connection with, this material. AIAPL, a company incorporated under the laws of Singapore with registration number 200813519W, holds a valid Capital Markets Services Licence to carry out fund management activities issued under the Securities and Futures Act (Singapore Statute Cap. 289) and Asian Exempt Financial Adviser for the purposes of the Financial Advisers Act (Singapore Statute Cap.110). Registered Office: 138 Market Street, #05-01 CapitaGreen, Singapore 048946.

In Australia, this material is being circulated by way of an arrangement with Aviva Investors Pacific Pty Ltd (AIPPL) for distribution to wholesale investors only. Please note that AIPPL does not provide any independent research or analysis in the substance or preparation of this material. Recipients of this material are to contact AIPPL in respect of any matters arising from, or in connection with, this material. AIPPL, a company incorporated under the laws of Australia with Australian Business No. 87 153 200 278 and Australian Company No. 153 200 278, holds an Australian Financial Services License (AFSL 411458) issued by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission. Business address: Level 27, 101 Collins Street, Melbourne, VIC 3000, Australia.

The name “Aviva Investors” as used in this material refers to the global organization of affiliated asset management businesses operating under the Aviva Investors name. Each Aviva investors’ affiliate is a subsidiary of Aviva plc, a publicly- traded multi-national financial services company headquartered in the United Kingdom.

Aviva Investors Canada, Inc. (“AIC”) is located in Toronto and is based within the North American region of the global organization of affiliated asset management businesses operating under the Aviva Investors name. AIC is registered with the Ontario Securities Commission as a commodity trading manager, exempt market dealer, portfolio manager and investment fund manager. AIC is also registered as an exempt market dealer and portfolio manager in each province of Canada and may also be registered as an investment fund manager in certain other applicable provinces.

Aviva Investors Americas LLC is a federally registered investment advisor with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Aviva Investors Americas is also a commodity trading advisor (“CTA”) registered with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”) and is a member of the National Futures Association (“NFA”). AIA’s Form ADV Part 2A, which provides background information about the firm and its business practices, is available upon written request to: Compliance Department, 225 West Wacker Drive, Suite 2250, Chicago, IL 60606.