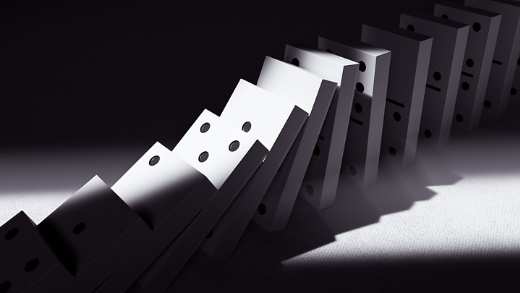

Rapid changes in the global economy could tip some sectors into low-carbon phases faster than incumbents expect, with important investment implications.

Read this article to understand:

- How systems thinking can identify tipping points

- How changes in energy, transport and food could radically reduce carbon emissions

- Super-leverage points that could be the target of intervention by policymakers

Given all the focus on the breakdown of political order, cost-of-living crises and assorted environmental challenges, it can be easy to forget how much the real economy is changing. In some areas, nascent technologies are displacing incumbents fast in a major boost for those seeking to decarbonise.

For economic historians, this is not a surprise. Technological disruption tends to start slowly then accelerate as new approaches become cost-competitive and ultimately cheaper than existing ones.

Many factors influence the pace of change, from hard limits on materials and ecosystem services to access to finance and social norms. The question then is: could policymakers and investors use their understanding of underlying processes to drive change faster, and get on the right side of it?

To find out more, we spoke to Professor Tim Lenton, founding director of the Global Systems Institute at the University of Exeter. As well as monitoring environmental tipping points (read more in Over(shooting) the limit: Why we need to keep within planetary boundaries), they are using a complex systems approach to look at the flipside: how to identify systems on the cusp of tipping to new, more efficient, lower-carbon states.1

We also hear from Nick Molho, Aviva Investors’ head of climate policy, on actions needed to accelerate the transition and get capital flowing into priority areas of the economy.

What do we know about climate and technological tipping points?

The climate system is on the cusp of major tipping points that could bring all kinds of unexpected, non-linear reactions. Given the policy backdrop, there is a lot of uncertainty about the outcomes; we need to accelerate efforts to decarbonise the global economy to make change about five times faster.2

To do this, we need to identify and trigger positive tipping points with strong feedback loops to force the system into a state of self-propelling change. The social elements are critical. The more we make something, the better we get and the cheaper each unit becomes. From the case studies we have, there are already examples of this taking place.

Technological reinforcement is part of the mix

Technological reinforcement is part of the mix. When a new technology emerges, innovation happens around it and other technologies appear that make it more useful. For example, there is no point having an electric car without an effective charging network and vice versa. To understand an entire system and its likelihood of tipping, we need to look closely at the main actors and what actions could bring the tipping about.

We have an interesting example in Norway, which has tipped towards battery electric vehicles (EVs) in the last ten years in an extraordinarily rapid transition, thanks to progressive tax policies (Figure 1). In Norway, it costs about the same to buy an EV as a petrol or diesel vehicle, but people have been smart enough to work out EVs are cheaper to run. So, Norway has shifted to EVs through policies targeting the total cost of ownership tipping point.

Figure 1: Tipping to electric mobility in Norway (per cent)

Source: Robbie Andrew, July 2023.3

Meanwhile, the global EV fleet is growing exponentially, doubling in about one and a half years. We now have about 17 million EVs on the road, but the world has about 1.4 billion cars. If we carry on with the existing doubling time (which we probably won't), by 2030 half the world’s fleet will be battery EVs.

Of course, there are other considerations. Some drivers may choose not to scrap their vehicles until the end of their useful life, but the data illustrates how quickly change is happening. That is a lot to do with the decline in the price of batteries through economies of scale. Even though battery prices went up in 2022 for various reasons – supply chain issues, the war in Ukraine and so on – it made no dent in the pace of growth.

What other areas could be important for tipping and accelerating decarbonisation?

Green ammonia is another area where there could be multiple reinforcing feedbacks between sectors (Figure 2).

Ammonia is the gas commonly used in fertiliser production; it is classified as green when the production processes are essentially carbon free.

Figure 2: Green ammonia and related super-leverage points

Source: Systemiq/University of Exeter GSI, 2023.

Most ammonia production today is not green because it involves steam methane reformation, where steam is used at a high temperature to split methane (usually fossil gas) into hydrogen, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. In a two-stage process, the hydrogen is then combined with nitrogen to form ammonia. It is very energy intensive and releases carbon.

How could we do this differently when we are producing a lot of renewable energy? There will be times when supply exceeds demand, and that excess energy can be directed to split water and create green hydrogen. Green hydrogen is one of many viable forms of energy storage to consider along with batteries if you want a 100 per cent renewable future.

Green hydrogen is one of many viable forms of energy storage to consider

If we look closely, interesting feedback loops emerge. Ammonia is used in fertiliser, but we don’t have to make fertiliser from steam methane reformation. We can use renewable energy to split water into hydrogen and oxygen and separate nitrogen from the air.

Because the price of methane has been high, green ammonia production is cost competitive with fossil-fuel fertiliser production. But by opening that market, we anticipate economies of scale. As capacity is built out, we expect the price of green hydrogen to come down enough to open a market where green ammonia could be as competitive as shipping fuel, replacing (fossil) bunker fuel. That is a larger market where it could be possible to achieve further economies of scale, bringing down the cost of green hydrogen further.

Steel production is another energy-intensive process and significant contributor to global warming. Using hydrogen in the production of steel, to make “green steel”, could also be part of a positive tipping cascade that could reduce emissions significantly.

Another area of interest is alternative proteins, where plant-based meat substitutes are coming to market that are competitive in terms of price and quality with real meat. We see evidence of exponential growth and expect fermentation-based alternative proteins hot on its heels. Lab-cultured meat has the potential to become a viable alternative as well (read more in Science fiction or reality: What investors need to know about cellular agriculture).4

Are the three tipping points you mentioned – EVs, green ammonia and alternative proteins – the most important?

The most fundamental tipping point is the one towards renewable energy. Our report was angled towards policymakers. From that perspective, zero-emissions vehicle mandates like banning petrol and diesel cars can trigger change across the whole economy. They can drive cheaper batteries to reinforce the renewable energy transition, as well as electrify goods and so on.

If the market is close to a positive tipping point, you could get more bang for your buck

A mandate for incentives like those put forward in the US Inflation Reduction Act for green hydrogen or green ammonia could also accelerate change. The potential shift to alternative proteins would liberate the land being used inefficiently by animal husbandry. This would help enable a necessary scale-up of carbon removal and storage by the biosphere. We could have other examples; our proposals were not intended to be definitive.

What is the significance in terms of getting ahead of change?

If the market is getting close to a positive tipping point, you could get more bang for your buck as policymakers or investors. You might make a modest policy change or shift in capital at a point in the system where there is strong reinforcing feedback with the potential to start self-propelling change. If your objective is to trigger a transition, you know when a particularly well-chosen intervention or incentive could have a disproportionate outcome (see Figure 3).

It is the same for investors. You might seek options to invest in the approach that is about to surge in a period of cascading change. There are risks and opportunities. We can use complex systems theory to guide on the risk-reward.

Figure 3: Interventions to trigger positive tipping

Social innovation

Technological innovation

Social-technological-ecological innovation

Policy intervention and public investment

Private investment and markets

Public information

Behavioural nudges

Source: Aviva Investors, 2023; University of Exeter GSI, 2022.5

Taking a step back, how do you assess the change going on across all sectors?

We have been building a research community with around 300 members. We recently released a report – The Breakthrough Effect – to address evidence of positive tipping points by sector, and the interactions across and between sectors where there might be reinforcing feedbacks.

The financial sector is vital because it could cascade change across many sectors simultaneously

This work has allowed us to identify “super-leverage” points that could be targeted through interventions by policymakers or other actors. Change in these areas could accelerate transition in sectors currently generating around 70 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions. The financial sector is vital because it could cascade change across many sectors simultaneously. We plan to release more details on this cross-sectoral study near COP 28 in December.

Change processes always experience roadblocks. How would you address roadblock shocks such as those around lithium mining?

Every new technology or innovation has environmental and social consequences. The big questions are how large the disruption will be and how will we manage the implications?

Every new technology or innovation has environmental and social consequences

Using lithium or cobalt for batteries kicks off environmental and social issues, because the transition is not always being governed as well as it could be. But those concerns should be smaller in the switch to battery driven vehicles than around coal mining or fossil-fuel extraction. In absolute mass terms, the scale is orders of magnitude different. For example, around seven million deaths a year are attributed to fossil fuel-related air pollution.

Is there any point applying tipping point analysis to macroeconomic data sets?

We do not believe traditional cost-benefit analysis or conventional macroeconomic analysis is relevant because we are in a time of transformation. Nobody needs to know allocative efficiency.

We need a different kind of efficiency, which is about the most effective way to act to create change. In that spirit, we prefer to model the market and the macroeconomy as a system where actors are not perfectly rational and core assumptions are not made.